Minor planet-based scientific astrological research has a lot of potential. Right now we have almost 25.000 named minor planets. Interestingly, name-based experiments can be designed in such a way that hermeneutical noise is minimized. In fact, minor planet names allow us to directly measure astrological meaning, by connecting the orbits of tiny little rocks to relevant (public) data sets. This explainer helps you navigate the minor planet space, so you can quickly zoom in on interesting subjects.

First things first: what does acausal semiotics even mean? Are words like symbolism or meaning not good enough? The reason ‘semiotics’ seems fitting when talking about the minor planet space, is that we find various modes of astrological signification working together simultaneously. Some are familiar to astrologers, others seem strange. Semantics doesn’t quite cover everything that’s going on. In linguistic terms, we should also consider syntax, and even the morphology of minor planet names. But at the end of the day minor planet astrology is always about observing and interpreting ‘signs’ in the semiotic sense.

Acausal implies a metaphysical commitment: it points to Jungian synchronicity as a speculative theoretical basis for explaining certain astrological correspondences. This is not to say that there is no room for classic ‘billiard balls’ causality in minor planet astrology, but it underlines the idea that typically, the limited causal impact of tiny little rocks orbiting the Sun can’t fully account for their astrological salience. The amount of semantic diversity, as well as the precision of the correspondences we encounter, demand a more reasonable explanation.

The term acausal semiotics can also point to a wider range of natural signification processes: Signs of the Gods in general if you will. For example, signs produced by following mantic procedures.

The role of the astrological community

Most people who ‘identify as’ astrologers are not particularly interested in minor planets, or asteroids. Only a handful of books have been written on the subject. Especially (1) Ceres, (2) Pallas, (3) Juno, (4) Vesta and (2060) Chiron are relatively well known. The reason for this might be that their mythological names, taken from the familiar Graeco-Roman pantheon suggest a kind of continuum. The fact that Ceres, Pallas, Juno and Vesta are important goddesses also surely helps. Before January 1st 1801, the day that (1) Ceres was discovered by the Sicilian monk Giuseppe Piazzi, the only feminine deity who owned planetary real estate was Venus. Also, (1) Ceres (see the header photo) is a sizable dwarf planet, which is reassuring for those who prefer to place their metaphysical bets on the laws of physics. The myths about Chiron, the centaur known as the wounded healer are again a natural fit for astrologers. Studying (2060) Chiron helps to advise clients on the healing of wounds; a non-trivial subject.

Need for astrological fluency

So far, astrological cookbooks about the five popular minor planets have tended to treat them as optional ‘extra planets’ and not so much as representatives of a new astrological space. Among other things, this approach might suggest that one has to be fluent in traditional astrology in order to be able to work adequately with (all of) the newcomers. For example, that one should understand the implications of (2060) Chiron in the 1st house, (2060) Chiron in Aquarius and so on. While there’s nothing wrong with doing that kind of exercise – in fact, it seems very organic – we should also acknowledge that in the minor planet space, we find both continuity and utter novelty.

I would especially like to remind all traditional astrologers who are reading this of two basic facts about the minor planet space. First: the ‘fabulous five’ have a far more complex semantic fingerprint than the average minor planet. When it comes to the complexity of the symbolism, there’s a huge range that goes all the way from ‘library full of stories’ to the relative banality of a licence plate or a traffic sign. Second, it’s unclear to what extent zodiac signs and house divisions are relevant in the minor planet space. Again, there seems to be a spectrum. My own observation is that for consistent relevance, we need to turn to the angles, lunar nodes, midpoints and other precisely defined points like lots (Arabic parts). When i reflect on this, especially in the case of tiny rocks, a point seems a much more natural fit than a 30° sector.

Harmonics and orbs

While the usefulness of certain traditional techniques for minor planet research is somewhat unclear, there can be no doubt that familiarity with harmonic aspects (conjunction, opposition, trine, square, quintile, sextile) is essential. For scientific research, a firm grasp of orbital mathematics is required. As a rule of thumb, minor planet-related astrological correspondences that are relatively easy to observe (in data sets) are indicated by important minor planet-to-planet aspects. The simplest example of an important aspect would be a conjunction of a minor planet and the Sun. In some sense, we can think of harmonic structure as the syntactic element of astrological meaning making and storytelling.

A quick word about orbs: as a rule of thumb, using a 1° orb is a good practice. Using a bigger orb for the Sun might be defendable. This might also be true for a few ‘heavy hitters’ like Eris and Sedna.

Case: Will Smith and the Oscars

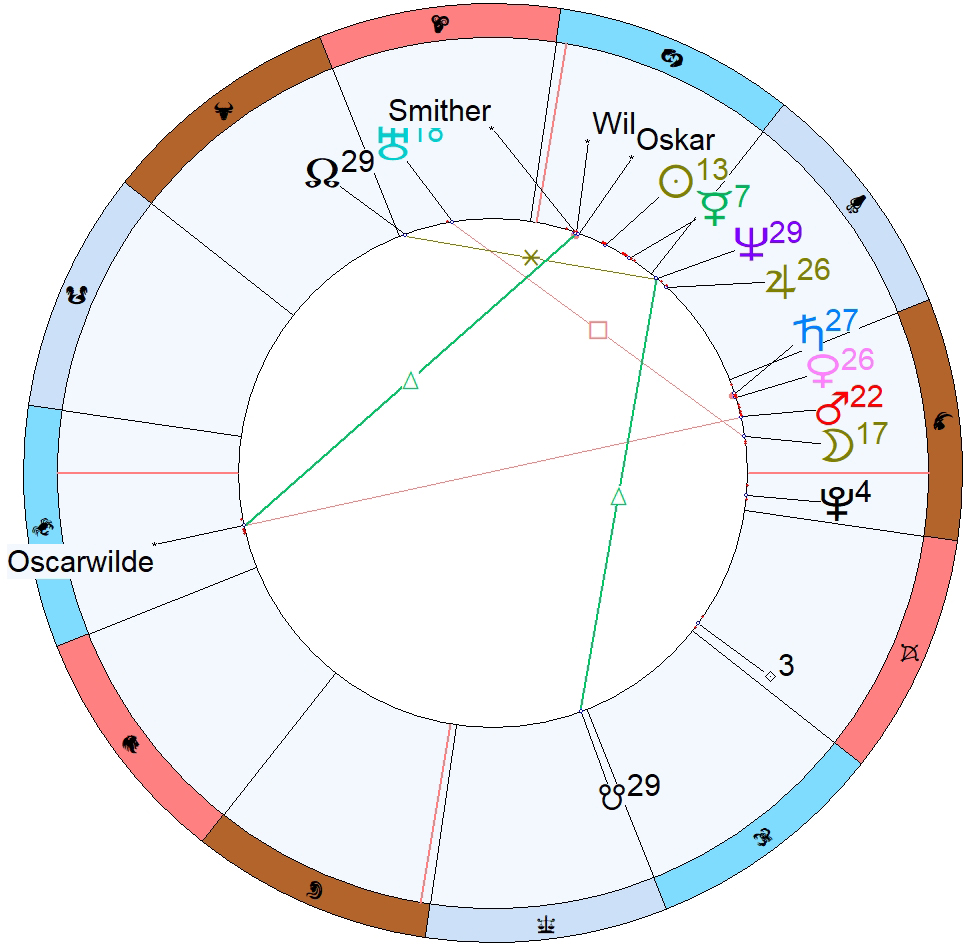

On March 27th 2022, in Los Angeles, USA, around 10 PM local time, American actor Will Smith slapped his colleague Chris Rock in the face during the yearly Oscars ceremony, after Rock made a joke about the hairstyle of Jada Pinkett Smith, Will Smith’s wife. The incident was shown live on tv.

The chart of the ‘Big Slap’ demonstrates the importance of conjunctions, and it also demonstrates how minor planets can produce signs on their own, without harmonic ‘assistance’ from planets so to speak. If you object to the seemingly incorrect spelling, please have a look at the section Morphological oddities below.

Fun facts: the diameter of (750) Oskar is 21 km, (2412) Wil measures 12 km, (2083) Smither is 6.6 km and (12258) Oscar Wilde 4.3 km. The triple conjunction is within 1°.

Ephemerides and software

At the time of writing, as far as i know, the most recent JPL ephemerides DE440 and DE441 have not been integrated in any astrological software (please correct me if i’m wrong). It used to be easy to download the old Swiss Ephemeris from Astrodienst for thousands of minor planets at a time but a few years ago FTP-access was severely limited, making it practically impossible to obtain a sizable collection of se1-files directly from the source. I am not aware of a solution for this problem that is supported by Astrodienst.

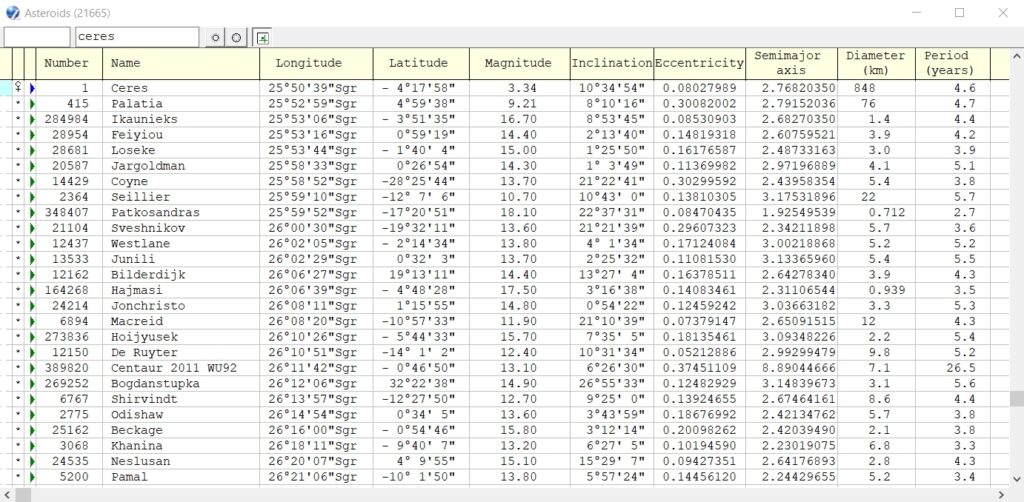

When it comes to minor planets there is no astrological software that ‘ticks all the boxes’, not even close. For scientific purposes Wolfram Mathematica seems to be the best solution. For casual browsing i recommend SkySafari 7 Pro, designed for astronomy enthusiasts. Personally, i use ZET 9 GEO to create charts like the one above. It has the dreaded Windows 95 look, it’s buggy and the user experience is awful, but it will load 20.000 minor planets or more and it allows sorting by number, name, longitude, latitude, period etc. which is a must have. Having said that, i can easily imagine a far more versatile app than this museum piece from the 1990’s. In conclusion, a satisfying astrological software solution for minor planet research doesn’t exist. This is not surprising: the astrological community isn’t really interested.

Minor planet taxonomy for astrological use

Below you find a rudimentary minor planet taxonomy, the emphasis is on categorization of named minor planets.

1. Astronomical classification

A straightforward way to categorize minor planets is to follow the standard orbit-based astronomical classification which is used in astronomical tools like the JPL Minor Bodies Database.

Dutch astrologer and minor planet specialist Benjamin Adamah has published a minor planet guide, in Dutch, containing over 950 minor planets, followed by (so far) four English translations, all based on the astronomical classification: Outer Main Belt Asteroids: Trojans, Hilda, Cybele, Plutino’s, Cubewanos, Haumeids and other TNOs, and Centaurs, Damocloids & Scattered Disc Objects. This is a logical way to look at minor planets, also for astrological purposes. Especially because, as Benjamin observes, these groups have certain qualitative characteristics in common. For example, according to Benjamin, the Cybele group is often about sexual themes, while Damocleïds point to disruptiveness. Plutinos mostly represent themes similar to those of Pluto.

Which brings us to another useful astronomical category: dwarf planets. For the mythologically fluent, this is a good selection of mythologically themed minor planets that includes important objects like Ceres, Eris, Sedna and Pluto.

2. Physical properties

The standard astronomical classification is orbit-based. Of course, we can also filter or group minor planets based on other physical characteristics like diameter, bulk density and so on.

3. Discovery date and/or number

Another formal way to categorize minor planets is by date of discovery, or number. This way, we again start with (1) Ceres, followed by (2) Pallas, (3) Juno, (4) Vesta, (5) Astraea and so on. Note that the numbering system has a few quirks. The observation of minor planets has its challenges and sometimes little mistakes were made. That’s why numbers and discovery dates do not line up reliably.

Just like dates of birth, discovery dates are also important astrological variables: discovery charts can reveal a lot about the semantic fingerprint of a minor planet. Although less important, a minor planet’s number can point to numerological meaning.

4. Named minor planets

The WGSBN or Working Group Small Bodies Nomenclature of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) is responsible for assigning new names to minor planets and comets, and announces these on a regular basis in a newsletter. Nowadays, the WGSBN does an excellent job, but in the early days of minor planet discovery, naming conventions and practices were more chaotic. Paul Murdin’s book Rock Legends explains how we got from Graeco-Roman deities to Star Trek references like (2309) Mr. Spock and (9777) Enterprise, or trivialities like (12426) Racquetball. Clifford Cunningham has also written about the early days of minor planet discovery, including lots of anecdotes about the naming process.

For scientific research, working with named minor planets is probably the logical choice, but it’s also possible to work with unnamed minor planets, as for example Benjamin Adamah has shown. If you limit yourself to named minor planets, you drastically reduce of the number of variables under consideration, which is probably a good thing. At the time of writing there are ‘only’ 24.785 named minor planets. Wikipedia does a pretty good job of explaining the meanings of minor planet names. The JPL Small Body Database also offers bits of information under ‘discovery circumstances’. Lutz D. Schmadel published many editions of the now discontinued Dictionary of Minor Planet Names which is still very valuable.

Categories of minor planet names

Once we commit ourselves to researching astrological correspondences involving tiny, causally impotent rocks bearing official names, we have to at least consider an acausal point of view. Because unless we’re talking dwarf planets or other objects with notable physical characteristics, the orbit, discovery date and name of a minor planet are the only salient astrological properties. And of course, names can’t be measured and described in physical terms. Both the official name and all of its relevant mental associations have no size, no weight, no colour, no temperature and so on.

The only ‘popular’ explanatory framework that works for minor planet-related astrological correspondences is Jungian synchronicity, which is a consciousness first, meaning-based type of theory. Personally, i recommend that you consider Bernardo Kastrup’s interpretation of Jungian synchronicity. Not just for it’s robustness, but also because Kastrup reduces synchronicity to a very simple, astrology-friendly principle that characterizes a basic mechanism behind astrological correspondences involving minor planets: association by similarity. For a better understanding, read Bernardo Kastrup’s book ‘Decoding Jung’s Metaphysics: The archetypal semantics of an experiential universe’.

Warning: while association by similarity is almost a kind of Rosetta Stone, this principle should be handled with care and used judiciously – only as a guideline or rule of thumb. There are quite a few exceptions and/or more complicated cases.

Now let’s try to categorize minor planet names. You may want to note that for the 2nd, 3rd and 4th category below, we’re primarily talking about minor planet names as significators. That is to say: pointing to specific people or places.

1. Mythological names

In the low numbers, the first category of names is mythical ‘beings’ or ‘gods’ from the Graeco-Roman tradition like (1) Ceres, (2) Pallas and so on. There is some continuity with the planet names. Because of the European obsession with ancient Greek culture and the Roman Empire, mythological beings from other cultures had to stand in line for a while, but eventually minor planets also got named after Sedna, Haumea, Tukmit, Apophis, Vishnu and so on. (42) Isis is in fact the first non-Graeco-Roman deity.

Mythological names are a relatively complex category because mental associations may include certain details from related mythological stories. In other words: if you’ve never read Hesiod and Homer, or are otherwise ‘mythologically challenged’ you might miss a few relevant signs or associations. Furthermore, we see some ‘semantic overlap’ and ambiguity. Quite a few deities are represented twice: both with the Greek and the Roman name. For example (399) Persephone and (26) Proserpina or (105) Artemis and (78) Diana. And while (78) Diana is named after the Roman goddess of the hunt, it’s also a common first name in many Western countries. It would be logical to look at this minor planet in natal charts of people named Diana, without necessarily thinking about hunting, bows, arrows and so on.

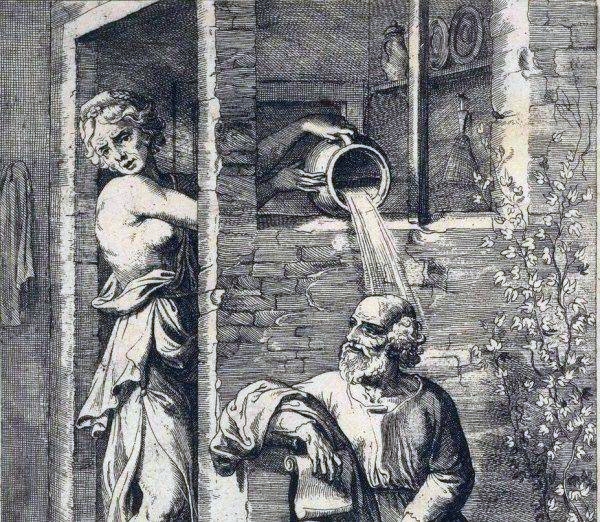

We can also zoom in on mythological sub-categories like the Greek Muses: (18) Melpomene, (22) Kalliope, (23) Thalia and so on. Or mythological sea monsters like (155) Scylla, (388) Charybdis, (1009) Sirene and (8813) Leviathan: anecdotally, these are for example associated with accidents at sea. And then there are famous duos like (624) Hektor and (588) Achilles, (156) Xanthippe and (5450) Sokrates, (18458) Caesar and (216) Kleopatra, or (18458) Caesar and (11302) Rubicon. Conjunctions of these kinds of pairs can be quite interesting. We can also group gods and goddesses from different cultures that ‘rule’ similar themes, like growth, wealth, conflict, violence and so on, although there will likely be both semantic overlap and some notable differences.

2. Common first names

Another category in the lower numbers are common (European, Latinized, often feminine) first names, for example (12) Victoria. Invoking the principle of association by similarity, we immediately suspect that this minor planet is also related to the concept of victory – which turns out to be correct (and helpful for the prediction of winners of sports matches and so on). Note that especially in the lower numbers, morphologically, feminine versions of first names are dominant, but at the same time experience tells us that semantically, minor planet names are gender neutral. This means that (12) Victoria is just as relevant for people named Victor or Vic, as for people named Victoria. Similarly, for people named Anton, Tony or Anthony, it would be logical to look at minor planet (272) Antonia, which is again the feminine form.

3. Names of famous people

Of the hundreds of minor planets named after astronomers (Lutz D. Schmadel quipped about the minor planet space being an “astronomer’s cemetery”) only a handful are named after famous astronomers like (697) Galilea or (1134) Kepler. Of course, there are many more minor planets named after famous people. Not only scientists like (1991) Darwin and (2001) Einstein, but also writers like (3412) Kafka and (5418) Joyce, actors like (2865) Laurel and (2866) Hardy, painters like (2662) Kandinsky and (4228) Picasso, composers like (1814) Bach and (1815) Beethoven, and so on. Names of politicians are not allowed, to avoid controversy, but that doesn’t mean that politicians can’t have significators. Quite the contrary! I will not give juicy examples here, again, to avoid controversy.

Wikipedia has a list of minor planets named after people. It has its uses but it’s incomplete and contains mistakes.

On that note, artist names can be a bit confusing. The musician Gordon Sumner aka Sting has been honoured with (601916) Sting, while Madonna Louise Ciccone got (34760) Ciccone. Composer/guitarist Frank Zappa got (3834) Zappa Frank, an unusual case of a last name followed by a first name, while Italian astronomer Giovanni Zappa simply got (16745) Zappa. Through association by similarity, Frank Zappa ends up with multiple significators. (5035) Swift is named after American astronomer and comet hunter Lewis A. Swift, but it also works for Taylor Swift.

4. Geographical names

Next are names of cities, countries, continents, rivers, lakes, mountains, volcanoes and so on. Typically there is very little ambiguity here – if the idea is to connect the minor planet name to the place ‘on the ground’ it literally refers to. Sometimes names are Latinized, like for example (1160) Illyria, which is a Roman name for the Croatian part of the Balkan region. And again there’s some overlap, for example in the case of (1160) Illyria and (589) Croatia, (21) Lutetia and (3317) Paris, or (1133) Lugduna and (12490) Leiden.

There are two useful Wikipedia lists: minor planets referring to places and to rivers – again, use with caution.

5. Psychological qualities

A slightly more complex category are descriptions of psychological qualities, often in Latin, like (58) Concordia – also a Roman goddess – signifying agreement or harmoniousness, (274) Philagoria, signifying fondness of assembly, (367) Amicitia, signifying friendliness, (975) Perseverantia, signifying perseverance, and so on.

Case: when association by similarity doesn’t work as expected

A minor planet name that doesn’t obey the principle of association by similarity in a straightforward way is (40) Harmonia. Sure enough it points to the concept of harmony, but with a twist, as it mostly points to unusual, edgy kinds of harmony. In music you might think of a complex jazzy chord with a rough but pleasing kind of dissonance. In fashion, think of an ‘imperfect’ model with a clearly noticeable gap between the front teeth, and so on.

Semantic oddities

So far we have been looking at names that signify ‘what it says on the tin’ as the British like to say. In other words: there’s a one-on-one relation between the (intended) meaning of the official name and core astrological associations. But associative processes can be much more complex and diverse.

The oddities that are discussed below point to a deep rabbit hole. We enter a zone where human language and the ‘linguistics of Nature’ slowly drift apart. To be clear, for scientific research all of this is optional, and to some extent it’s speculative. But having said that, it doesn’t hurt to explore and sharpen your intuitions. Although some of these quirks are unique to minor planets, they can also enrich our general understanding of the mechanics of astrology. My personal impression is that everything points to a deep integration of various modes of signification, all working in sync, paired with a ‘natural desire’ to communicate symbolically and linguistically. The result is a rich tapestry of astro-entrained meaning that simply boggles the human mind. Going forward, epistemic humility is advised.

Interesting last names

Lots of minor planets are named after scientists. Especially in the higher numbers, it is quite common to see minor planets named after both the first and last name of an astronomer. For example (81859) Joe Taylor, an American astronomer and Nobel laureate. Although Mr. Taylor is a great astronomer, the associative potential of his name scores below average. In contrast, especially in the lower numbers, we find minor planets bearing only the last name of a scientist, and some of these are ‘interesting’. For example, (8690) Swindle is named after meteoriticist Timothy D. Swindle and (26955) Lie is named after the Norwegian mathematician Marius Lie. As the association by similarity-principle suggests, these minor planets primarily indicate certain kinds of dishonesty. In other words: what it says on the tin, but much more disconnected from the eponym, and much less a significator for a particular person. Other examples are (1941) Wild, named after Swiss astronomer Paul Wild and (27719) Fast, named after mathematician Wilhelm Fast, and again (5035) Swift.

Lost and found in translation

Linguistically, the minor planet space is not just Graeco-Roman or English. It’s international. Besides the European names, there are plenty of references to Chinese, Russian, Indian, African, Arabic, South American and Oceanic people, places, events, deities and so on, but that’s actually a relatively superficial kind of linguistic diversity. If we dive deeper, and again invoke association by similarity, it turns out that astrological signification is to some extent language-agnostic. A minor planet name may point to multiple, different meanings, but in different languages, because of the different associations evoked by the same string of alphabetical characters, especially if it’s a short string. For example, (6049) Toda is named after Japanese astronomer Kojun Toda. In Japanese, at least according to online sources, Toda is a surname, a place, and it also means ‘door’ and ‘rice paddy’. But in Spanish, toda is the feminine form for ‘all’ or ‘everything’. And there’s a pretty good chance that toda has other relevant meanings as well in other languages besides Japanese or Spanish, that translate into certain observable astrological correlations. In practical terms, this means that cataloguing the meanings of minor planet names has to be an international effort. We can’t assume that knowing English and some mythology is enough to understand what’s going on with the semantics of minor planet names.

Nameless minor planets

It’s perfectly possible to work with nameless objects. To give just one notorious example, (15874) 1996 TL66 is associated with winning lots of money in a lottery.

No clear association ‘by similarity‘

If you familiarize yourself with the work of minor planet specialists like Benjamin Adamah, you will come across names that seem unrelated to their astrological associations. An example would be (7248) Älvsjö, named after a suburb of Stockholm. Somehow it is a very reliable significator for electricity-related trouble, like for example power outage or short circuiting. The connection with the name is unclear (to me), and so this example demonstrates that the principle of association by similarity may have its limits.

Morphological oddities

To some, the word ‘oddity’ might seem a bit of an understatement when it comes to morphological issues. Minor planet name linguistics has it’s own laws of entropy and i will be the first to admit that it gets really ugly really quick. Especially for those of us who appreciate correct spelling. But on the other hand, we have to admire Nature’s desire for communication, storytelling and meaning making. When nothing else is available to get a certain message across, slightly damaged syllables will have to do.

Nature doesn’t care about correct spelling

Incorrect spelling of minor planet names is trumped by correct mental association. Certain Virgos will simply have to learn to live with this. To give a simple example: (155) Scylla, (388) Charybdis and (8813) Leviathan are what-it-says-on-the-tin references to mythological sea monsters. But we may also add Makara (of Capricorn fame) to this trio, represented by minor planet (32278) Makaram, named after Yashaswini Makaram, a finalist in the 2016 Intel Science Talent Search. In a somewhat similar way (750) Oskar may refer to people named Oscar, or even to an award for artistic or technical merit for the film industry.

Getting the first syllable right is quite often good enough

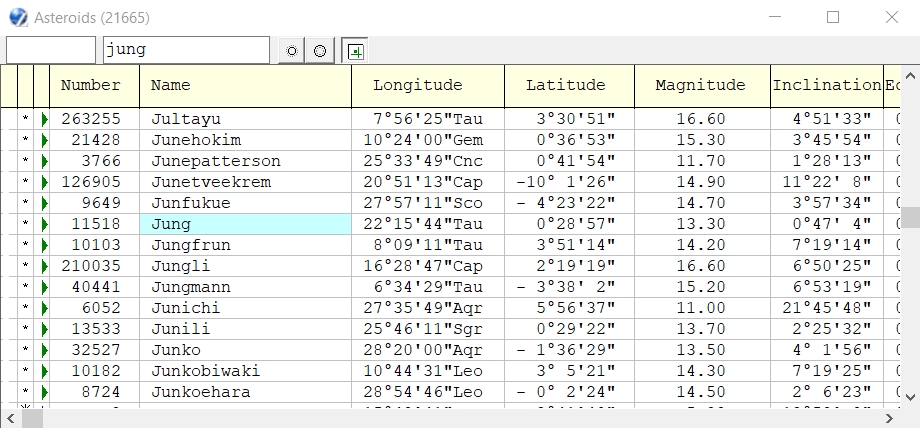

If you study C. G. Jung’s chart, you will notice that the Swiss psychiater has a personal significator (11518) Jung that does what it says on the tin, but also a second important significator (210035) Jungli, that works just as well. (210035) Jungli is named after the Zhongli District, located in Taoyuan, in the north-western part of Taiwan. Apparently, one significator is not enough to tell the story of C. G. Jung and morphologically, (210035) Jungli seems to be the ‘next best’ option, followed by (40441) Jungmann.

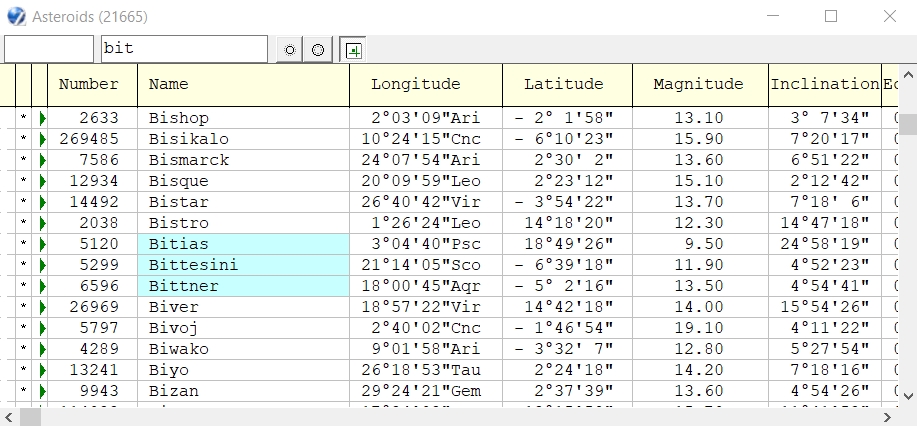

If you are into financial astrology, you might be interested in significators for companies, stocks, commodities, funds and so on. Let’s say you want to find significators for Bitcoin. The general rule is that if you can’t find a what-it-says-on-the-tin candidate – in this case a minor planet literally named ‘Bitcoin’ – you can try names that start with ‘Bit’, because getting the first syllable right is quite often good enough. The most obvious significators for Bitcoin are (5120) Bitias, (5299) Bittesini and (6596) Bittner. It turns out that each one has it’s own semantic fingerprint, reflecting a different aspect of the adoption of Bitcoin. Whenever there is an important Bitcoin-related event, like for example Pizza Day, these three significators have something to say.

Acausal oddities

Numerology

Numerological signs are not very common in minor planet astrology, but they do exist. There’s creepy symbolic stuff, like the fact that Adolf Hitler’s natal chart has (666) Desdemona exactly on the MC, but there are also other kinds of examples. Astro-numerology is not a really important subject in my opinion, but the fact that there can be a numerological ‘layer’ at work clearly points to the deeply integrated nature of minor planet semiotics.

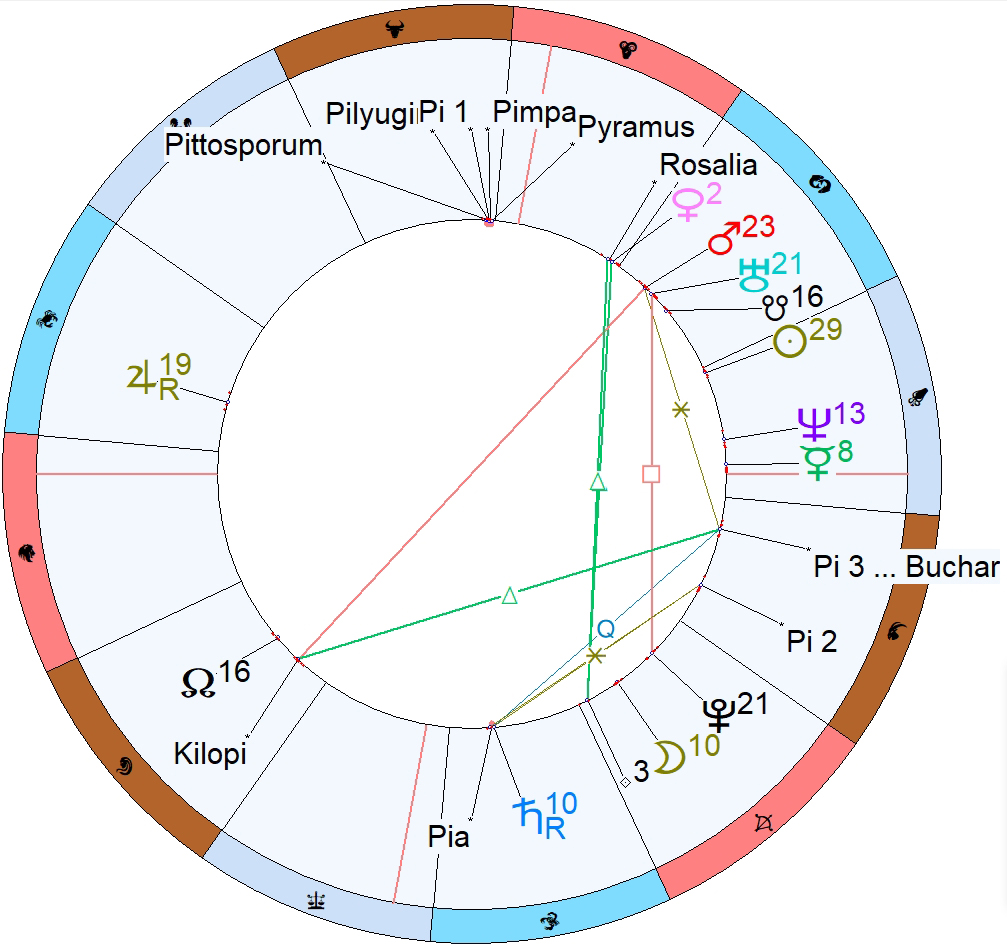

Case: Pi day 2015

Math enthusiasts celebrate Pi day on March 14th, since 3, 1, and 4 are the first three significant figures of π. In the year 2015, a ‘Super Pi Day’ occurred, as the date is written as 3/14/15 in month/day/year format.

The first 6 digits of π are 3.14159. Translated into minor planet numbers, this yields:

Unnamed Pi significator 1: 314159;

Unnamed Pi-significator 2: 31415;

(3141) Buchar;

(314) Rosalia.

And we may also add:

(3142) Kilopi, a name that means 1000 x π (rounded off);

(614) Pia, a non-numerological reference.

What we get on ‘Super Pi Day’ might not be super convincing, but it is a non-random configuration: (314) Rosalia conjunct Venus, (614) Pia conjunct Saturn, and Pi significators 31415 and (3141) Buchar aspected by Saturn and Pia. It seems that unnamed significator 314159 is not involved, but on closer inspection, it turns out that it’s conjunct three minor planets that have names starting with Pi, and one starting with Py. And (3142) Kilopi is aspecting Buchar and Mars.

Collective meaning making

Another characteristic that points to the integrated nature of minor planet semiotics is its collective aspect. It is very common for people, topics, and events to be represented by multiple (groups of) minor planets, creating multiple ‘pockets’ or ‘clusters’ of associations and meaning. This is somewhat different from the classic interrelatedness of planets, signs and houses, especially in that it is more specific. The Pi day example above illustrates this idea to some extent.

Retroactivity

The first minor planet was discovered in 1801. Hundreds of thousands of minor planets followed. For minor planet specialists, there is no doubt that astrological signification involving minor planets also ‘works’ before 1801. In other words: the names are backwards compatible. This may sound like an anomalous phenomenon, but synchronicity should be thought of as a mode of patterning or structuring that permeates the physical world in ways that can transcend time. In fact, this particular kind of retroactivity is nothing new in astrology. Uranus, Neptune and Pluto are also routinely thought of as backwards compatible.